Building an Internet Oasis in Baltimore’s Black Butterfly

An effort to bring connectivity to community centers during the pandemic now serves thousands of people around the city.

At the Transformation Center, a community outreach center in Baltimore’s Brooklyn neighborhood, a growing number of residents line up for food, diapers, and other essentials. Since the pandemic began, it’s been a common scene across the United States, but at the Transformation Center, there’s a notable exception. As clients get in line for what is often a 45-minute wait, they pull out their mobile phones, ready to take advantage of the free Wi-Fi. It’s been available through a community network since May 2021, thanks to a dedicated group of local heroes.

“A lot of people don’t have enough. They barely have the bare minimum,” says 21-year-old Mohammed Saheed Aiyeloja.

“If I buy a bus pass for the week and two days from now, I don’t have enough Internet on my phone, then I can’t show it to the bus driver,” he says. “Now, we can come in front of the church to get Wi-Fi or in front of the community center to do work where we are safe. That’s the tool that helps with everything.”

Mohammed is more than just a community network user. He’s also part of the core team that’s been installing hotspots around the city.

The Transformation Center is one of the seven locations for the network. Since 2020, the Wi-Fi hotspots have been installed through a partnership between Rowdy Orb.it, United Way of Central Maryland, Elev8 Baltimore, No Boundaries Coalition, and the Internet Society’s Greater Washington DC Chapter.

“I was kicking the idea around… and we knew people didn’t have reliable Internet. So, I was like, ‘there’s got to be a better way to do it and a cheaper way’. I just didn’t know how,” says Jonathan Moore, CEO and founder of RowdyOrb. it, a Baltimore-based tech firm focused on expanding digital access and training.

He wanted to reach the city’s most underserved neighborhoods.

Baltimore: A Tale of Two Cities

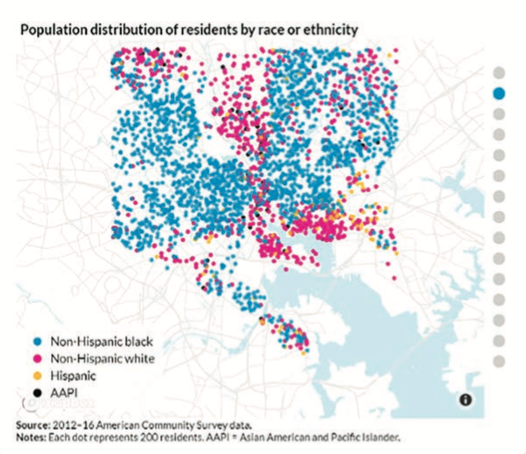

Baltimore’s affluent, well-serviced, and predominantly white neighborhoods stand in stark contrast to its poor, under-resourced, and predominantly Black communities, which fan out across the city’s eastern and western halves in near symmetry, like the shape of a butterfly’s wings.

Baltimore’s pattern of racial segregation has been described by Morgan State University Associate Professor Lawrence Brown as “the Black Butterfly.” Communities within the western and eastern wings of the Black Butterfly must contend with racial inequity, crime, health disparities, and poverty.

“They’re two neighborhoods that mirror the exact same disparities,” says Moore.

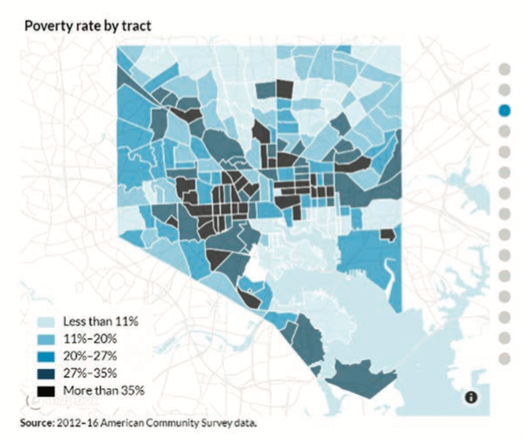

According to the 2020 US Census, Baltimore has an average poverty rate of 21.2%—roughly double the national average and one of the country’s highest.

The “Black Butterfly” refers to the distribution of the Black population in the city. Source: Urban Institute

Poverty rates are below 11% in the city’s predominantly white northern neighborhoods. Within the Black Butterfly they often exceed 35%.

“Baltimore is the tale of two cities: one of poverty and one of fancy,” says Alexandria Adams, executive director of Elev8. “If I were to paint the picture of systematic racism, it is concentrations of hyper poverty, where you have large pockets of people with no access to resources.”

It’s a disparity that’s rooted in policies from generations ago. In 1910, the Baltimore City Council passed a housing segregation law establishing certain neighborhoods as white or Black. In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration began color coding neighborhoods according to their creditworthiness. Predominantly Black neighborhoods were marked red, which cut them off from access to mortgages—a practice known as “redlining.”

Source: Urban Institute

Investment across Baltimore is also uneven—fragmented by race, income, and geography. Neighborhoods that are less than 50% African American receive nearly four times the investment of neighborhoods that are over 85% African American. Low-poverty neighborhoods receive one and a half times the investment of high-poverty neighborhoods.

The pandemic has only amplified the inequality, says Jonathan. “The number of people getting food is on the rise, and there are also more people taking public transportation … It’s impactful how hard hit a lot of the communities we serve are because of COVID-19.”

Baltimore’s Digital Divide

When it comes to Internet access, the numbers show similar disparities. A May 2020 report noted that 40.7% of households in Baltimore do not have wired Internet service—in other words, cable, fiber, or DSL. One in three households have neither a desktop nor laptop computer. The report also notes Baltimore’s 29th ranking out of 33 U.S. cities for home wireline broadband adoption.

Not surprisingly, Internet deserts are common across the Black Butterfly. Jonathan says Internet fibers in many communities aren’t for home service, but for police surveillance. At the same time, he says some people see the addition of new Internet infrastructure as a beacon of future displacement.

“As soon as you start to see groups of construction workers and utility trucks coming into your neighborhood, that’s a sign that it’s slated for gentrification and a canary in the coal mine. It’s a sign that you are going to be displaced if you don’t own,” says Jonathan.

It’s a perception he and other people trying to connect underserved communities must fight. Free community Wi-Fi is a way of fighting, rather than aiding, gentrification.

“Usually when something goes into a community, there’s a sense of ‘well, how much are they extracting?’ versus ‘how much are they leaving?’ But we wanted to focus on community ownership. By us leaving more, we’re seeing a significant economic footprint,” says Jonathan.

It may take time to develop trust with a community network … but once you do, there’s rapid growth.”

Mohammed, who grew up in Baltimore for most of his life, agrees. “The first step is just us showing up and showing that we are trying to do something for [the community…] we stand for them and with them.”

How the Partnership Began

In 2019, a conversation during a digital equity conference in Washington, D.C. sparked the partnership behind this community network. It later led to a connection between Jonathan Moore and Dustin Loup, executive director of the Internet Society Greater Washington DC Chapter.

“He had this vision for building a community network in Baltimore, but making it more than that, with locally owned infrastructure that could be leveraged for other things like air-quality sensors,” says Dustin. “I liked his approach. It wasn’t just about connectivity as a buzzword, but what it could do for a community.”

Jonathan wanted to prioritize free Wi-Fi hotspots in Baltimore’s most underserved communities and eventually expand to provide access across the city. He originally envisioned laying fiber, which is complex and expensive. “I was like, ‘there’s got to be a better way to do it and a cheaper way.’ I just didn’t know how,” he says.

The Internet Society showed him an alternative. “Dustin and I went up to New York and NYC Mesh and did an install and I was like, ‘Oh! I see. OK, this is how you can do it.’”

Jonathan joined Dustin for an Internet Society workshop in October of 2019. From there, they applied for what was then an Internet Society “Beyond the Net” small grant to fund training for three high school students.

The training, on networking basics and configuring networking equipment to create access points for a community network, took place in February of 2020—just before the pandemic forced many in the United States into quarantine.

But far from hindering the community network, Jonathan says the pandemic helped. “As sad as it was, that’s what it took. Now, we didn’t have to convince people[…] as to why this was important … so that’s like eight conversations that you don’t have to worry about.”

Connecting Community Schools

A few weeks after the initial training, they organized a follow up with the same students who had configured the networking equipment. This time it was to teach them how to install it. New Song Academy, a school run by a community organization, offered the roof of their building for the first community Wi-Fi antenna in March 2020.

Having the free Wi-Fi signal early in the pandemic helped several families who were struggling. Doug recalls one parent who came by to print a form so she could apply to social services. While in the building, she realized she didn’t have data left on her phone, so she couldn’t forward the document. When Doug showed her how to connect to the free community Wi-Fi, she was able to forward the document, check her email, check news websites, schedule doctors’ appointments, and retrieve her messages.

It was an eye-opening moment for Doug, who called it “the kind of access that I, as a middle-class white guy living in Charles Village, just simply take for granted.” But it’s energized him. “If you could just get connected, your world would be changed. … This is something we want to continue to pursue so that our residents can have everything that residents of more affluent communities have.”

Doug says there are only a handful of free public Wi-Fi hotspots around New Song’s neighborhood, Sandtown, compared to at least 50 in Charles Village. And few homes in Sandtown are connected.

“That is a reflection of race-based decision-making in city planning. I mean, let’s just call it what it is,” he says. “There is not the same need seen here as there is in other communities. But actually, there is the same need and the same desires … for all those things that a lot of communities take for granted.”

In the first few months of the pandemic, New Song became a hub for food distribution, serving 500 lunches a day, five days a week.“To anyone who stood in line who had their phone out, I would say, ‘Hey, if you want free Wi-Fi, just click on this thing’. Our families knew that if they needed to, they could pull up, open their laptop and get to work,” says Doug.

Students installed the first community Wi-Fi antenna at the New Song Center in March 2020. © New Song Academy

“We know that a lot of people are using the free Wi-Fi hotspot during the third and fourth week in a month when things get real tight because of their data package. They run out of data. Now, they have [a centrally located] place to go and get connected ,” says Jonathan. “You know, I just thought we were throwing up an antenna … but it just turned into a much bigger thing.”

But to be impactful, they needed to expand the community network beyond New Song. The next Wi-Fi hotspot was installed in June 2020 in Cherry Hill, south Baltimore. Its location, Elev8 headquarters, provides out-of-school opportunities, school-based health services, resources, and community outreach.

Around that time, the team applied for another grant from the Internet Society. They were awarded US$22,000 to order more equipment, which enabled them to put up more hotspots.

The next installation was at the Patapsco Elementary School in Cherry Hill. It provides connectivity for a half-mile radius.

By then it was clear that trained high school students couldn’t provide the full-time workforce required. To meet the gap, Jonathan and Elev8 came up with a workforce-development plan. They approached the Maryland office of the nonprofit NPower, which provides technology training to military veterans and young adults from underserved communities. NPower connected them with people who could work part-time starting in July.

Workforce Development through Community Stewards

By September 2020, the project had hired four NPower graduates as full-time RowdyOrb.it consultants. The employees were tasked with building out more networks, with the goal of becoming long-term stewards.

“Our goal is to train people, building local worker-owned cooperatives, and create a sense of community ownership,” adds Jonathan.

Alexandria says adding a workforce-development component is key for long-term sustainability. Elev8 and the United Way of Central Maryland provide soft-skills development while RowdyOrb.it and the Internet Society impart the hard skills on community network installation.

“It’s about us facilitating a long-term opportunity to dismantle institutional racism,” says Alexandria. “Out of these negative things comes a workforce of people who understand Wi-Fi. It’s not just ‘oh, I can be a technician, but I can be an owner.’ That’s the definition of reclamation and for me that’s what most exciting about it for me.”

It’s about us facilitating a long-term opportunity to dismantle institutional racism.”

One of Jonathan Moore’s protégés is Jonathan Butler, 27, the area installation manager at RowdyOrb.it. Just two years ago, he had no Internet access.

“I was working at T-Mobile as a salesman. I was working at Corner Bakery. I worked as a substitute teacher. I worked all over, just trying to figure things out, but it wasn’t easy and it was getting to the point where things were just dire,” recalls Butler. “We didn’t have Wi-Fi [or Internet] at all… because my parents were older, so they didn’t feel the need. That was a big thing because I would go back and forth to friends’ houses just to get Internet, or borrowed it from neighbors… It was honestly a struggle.”

While online one day, he came across NPower, the only local trade school accepting older students. After six months of training in information technology, he got a placement at RowdyOrb.it. He started working on the community networks project in July 2020.

Jonathan Butler, left, works on an installation at the City of Refuge in November 2020. © Baltimore Sun

“Once we actually started doing the work, I just fell in love with it. Not only do I feel like I’m engaging with people and doing something that’s positive for the world and giving back, I also feel that I’m learning… It’s only the tip of the iceberg when you talk about the digital divide,” says Butler.

He recalls how one mother was brought to tears after getting free community Wi-Fi. She had been unconnected for a while and her children couldn’t go to school. There was also the father in Curtis Bay who was thrilled to discover he and his children could access the Internet from his front porch—rather than paying for expensive mobile hotspots.

I can’t really think of a more fulfilling job. You really understand how many people’s lives you’re touching. It just makes you want to work a lot harder.”

“This job gives me hope because I see people who look like me helping people who look like me. And it’s rewarding, because we can fix our problems.” adds Butler. “I’ve always been passionate about helping the community because I come from an area that doesn’t have many resources and I understand how that can really affect the course of your life. It can make or break you.”

Mohammed tells a similar story. At 21, he’s the youngest steward. “I feel like technology and digital equity is an equalizer for a lot of people because there are people that build multimillion-dollar businesses off their phone.”

He says his technical and personal skills have also expanded. “I knew I wanted to help people but I had to be more hands on. It has made me a better person because a lot of the things I do right now I didn’t know last September: the building of the antennas, the configuration events and the antenna masts, the different types of hotspots, different types of RF radio.”

Connecting Community Centers

The project got another boost when their work adding Wi-Fi hotspots to the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and United Methodist Church—both in Cherry Hill and both heavily involved in providing goods and services to the community—was featured in a newspaper article. After reading about their ground-breaking work, the local United Way contacted the team to get involved.

“United Way of Central Maryland brought in additional funding for a long-term, backhaul solution plus workforce development and ongoing compensation for the people being trained and doing the work,” says Loup.”

United Way’s support of this work—co-created with residents and community leaders—drives positive change from the ground up. People who live in the neighborhoods served can be trained and hired to sustain an ever-growing infrastructure for their communities, while sustainability is driven by these localized workforces. This in turn influences community revitalization and strengthens local economies.

The United Way also connected the team with the Curtis Bay community – which has difficult terrain, made up of rolling of hills and few tall structures to amplify Wi-Fi signals. The team started by connecting the City of Refuge community center in November 2020, which serves more than 700 clients per week for food services alone.

Dustin says many of the hotspots were strategically placed in safe spaces that provide valuable resources to the community. “There are a lot of people who don’t have stable housing, so they need to know that there are places where they can have an open and safe connection.”

Two hotspots have been installed near homeless encampments. The team works with community organizations to identify where to install the free Wi-Fi hotspots.

Heather Chapman, Vice-President of the United Way Neighborhood Zones in the Central Region of Maryland, says this community involvement in decision-making is key. “Often when you talk about the digital divide and digital equity, you don’t see that conversation equitably happen. You don’t see Black and Brown people at the table, and that’s why we were intentional about this being inclusive.” She adds, “When we speak about our project, we always use the words digital equity, because that’s really what it’s about.”

A Curtis Bay resident logs on to the free Wi-Fi at the City of Refuge community center to check his email and continue his job search. © Kara Nicole/City of Refuge.

You don’t see Black and Brown people at the table, and that’s why we were intentional about this being inclusive.”

The United Way’s first community centers got hotspots in February 2021. The latest installation was at the Transformation Center in the Brooklyn neighborhood in May 2021.

Curtis Bay resident and youth leader Tarriq Thompson, along with his mother and sister, had been sharing his sister’s personal Wi-Fi hotspot. It wasn’t enough. “It’s been really hard, especially since COVID and everything, to work from home. I’d rather do interviews on my phone with just data, because the Internet is either bad for me or there’s none at all. Internet is the key to our success right now.” He’s happy about the new community Wi-Fi.

Home Connectivity

Heather says expanding into homes and ensuring the quality of Internet connections is also essential. “There’s still a huge divide because even in many of those communities, where there are people of color, where people are disenfranchised, [Internet] connections are still not enough for people to be able to do what they need to do,” she says. “It’s not just about connectivity but about quality of connectivity.”

Mohammed Aiyeloja, top left, and fellow stewards work on one of the home installations in Curtis Bay in July 2021. © Jonathan Butler

After getting the United Way funding, the team secured backhaul from a medium-sized ISP (GiGstreem) for a wireless point-to-point link from across the Patapsco River.

They’ve now started expanding the community network to homes. Their goal is to connect one home per day, reaching 210 in the first year. Each hotspot covers approximately a half-mile (800-meter) radius, with homes selected based on their location between two air fiber points—high-speed and fixed-location data transmission using radio waves. The installation of these home-based hotspots began in Curtis Hill in June 2021 and is expected to take five months.

Jonathan says equipment and access will remain free to all participating households and users for the first year. Ultimately, though, Dustin and Jonathan hope to build a sustainable cooperative business model. One that can be owned and managed by community members, while keeping the cost affordable.

The community Wi-Fi hotspots currently serve some 2,000 people per week. Once the home expansion is complete, they’re expected to able to reach more than 6,000 per month.

It’s a step in the right direction for achieving digital equity—on the community’s own terms.

Leading image: © J.J. McQueen