Authors: Mark McFadden, Sam Wood, Robindhra Mangtani, Grant Forsyth

Note: The report is an independent study that the Internet Society has commissioned to an external consultancy.

Executive Summary

The Internet of Things (IoT) is a vast network of physical devices – including consumer products, durable goods, cars and trucks, industrial and utility components, sensors and other everyday objects – that have been fitted with Internet connectivity and tools for the collection and exchange of data.

Adding connectivity to physical devices can significantly expand their usefulness: for instance, it can allow remote operation or monitoring of the device, improve user convenience, or enhance energy efficiency. As a result, the number of connected IoT devices has grown rapidly: according to some estimates, the number of IoT devices in operation in 2018 surpassed 10bn.[1]

This growth has been accompanied by increasing concerns about cybersecurity and privacy. Nowhere is this more true than in the consumer IoT segment. This segment – consisting of connected devices intended for personal or residential use, such as smart TVs, connected appliances, voice assistants and home automation devices – accounts for an estimated 63%[2] of the total installed base of connected devices, and is growing quickly.

Security is often lacking in consumer IoT devices: an analysis of 10 of the most common types of consumer devices – including smart TVs, home thermostats, and connected power outlets, door locks and home alarms – found that 70% contained serious vulnerabilities.[3] Potential vulnerabilities include the transmission of unencrypted data over the Internet, insecure software update processes, and the use of non-unique and easily guessable default login credentials. [4]

The exploitation of these vulnerabilities can cause direct threats to the device owner’s safety and privacy. [5] For example, in 2015, a researcher reported how he was able to remotely hack into two connected insulin pumps and change their settings so that they no longer delivered medicine.[6] In 2018, a number of connected toys were found to be easily hackable, giving an attacker access to the microphone and location data. And in November 2016, an attack was carried out on a connected heating distribution system in Lappeenranta, Finland, disabling the heating in two buildings.[7]

Insecure devices also present risks to third parties. For example, a compromised device may be enrolled into a botnet – a network of thousands of infected Internet-connected devices under the control of an attacker. Botnets may be used to send spam, distribute malware, commit online advertising fraud, or commit Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. [8] DDoS attacks can be used to take websites offline, causing substantial cost to the victim and disruption to users and the wider Internet.

There are a number of technical factors that make consumer IoT devices and services vulnerable to attack. Ultimately, however, weak IoT security has its roots in economic factors rather than technical ones. These include:

- Asymmetric information. It is often difficult for consumers to discern IoT products with good security from those with poor security. As a result, manufacturers are not rewarded by consumers for investing in effective security measures.

- Misaligned incentives. The costs of a security breach of a consumer IoT device or service are borne by the device owner (and wider society), not the manufacturer or service provider. For example, IoT enabled door and garage locks can be compromised to give an intruder access to a property, but typically the manufacturer does not face the consequences of this intrusion. As a result, manufacturers do not have strong incentives to include effective security in their products and services.

- Externalities. Compromised devices can be used to conduct attacks on third parties. This imposes costs on the target of the attack (and on wider society) which are not borne by the device owner, the manufacturer or the service provider. None of these parties will factor these costs into their decision making. This is termed an externality.

As a result of these economic factors, manufacturers are likely to under-invest in security measures. Instead, they will prioritise lowering costs and getting their products to market quickly. Including effective security costs money and slows down the product development process. In addition, it requires specialized skills and experience which manufacturers may not have at hand, requiring either new staff or external consulting – both of which increase costs.

To improve the state of security of consumer IoT devices and services, action will need to be taken to address and compensate for these factors. To be effective, any solutions are likely to require engagement from policymakers and industry. In addition, these solutions will have to strike a balance between improving security and allowing scope for innovation and evolution within the market.

Below we suggest a number of potential actions to address the economic factors. These actions are intended to improve the security of consumer IoT devices and services on the market, and to encourage manufacturers to adopt a ‘security-by-design’ philosophy, where security is considered at all stages of product development, sale and ongoing support. This set of potential actions has been developed after consideration of a wider number of mechanisms for improving security on consumer IoT devices and services.[9]

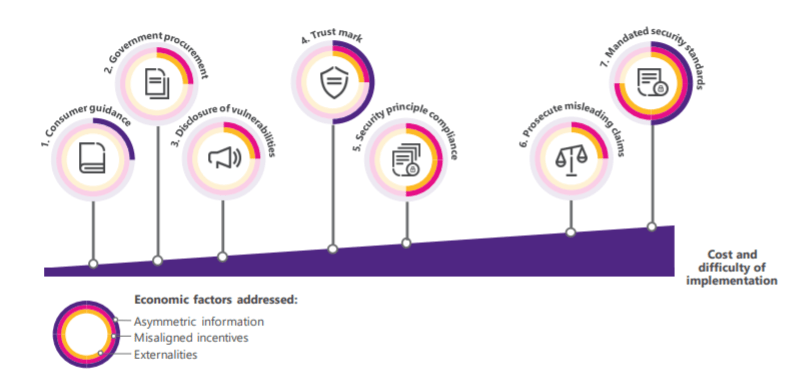

The actions are illustrated in Figure 1. They are listed in order of the likely cost and difficulty of implementing the action. Figure 1 also denotes the efficacy of each action in alleviating (or compensating for) each of the three economic factors behind poor security on consumer IoT: asymmetric information, misaligned incentives and externalities. The actions are aimed at a variety of stakeholders in the market – indeed, actions taken by different stakeholders will complement each other and help drive greater improvements to security. Security measures in the actions are taken to refer to security against both inward and outward threats, in order to protect both the user, third parties and the wider Internet.

It is important to acknowledge that the risk from insecure consumer IoT devices is a global problem: while one country may take steps to keep insecure IoT devices off its domestic market, it will still face risks from insecure devices in other jurisdictions. Growth in connected devices across the world will likely lead to increased transnational liability, security and privacy issues, which existing legal cooperation frameworks may be illequipped to handle. Cross-national, regional and global multi-stakeholder efforts to enhance consumer IoT security should be encouraged where possible.

Figure 1: Potential actions and their efficacy against the economic factors behind poor IoT security

The potential actions are discussed in greater detail below.

1. Industry bodies and policymakers should prioritise raising awareness of consumer IoT security issues, and provide guidance to buyers. Providing information to consumers on the possible impacts of insecure devices and the need for them to seek out secure devices and services will empower consumers to make better buying decisions and help correct information asymmetry in the market. For example, in the UK, the Information Commissioner’s Office provides such guidance for consumers considering buying IoT products.[10]

2. Governments should specify a set of security outcomes for their own procurement procedures. Governments can and should leverage their role as major purchasers to incentivise manufacturers to improve their product. These improvements in security may spill over into the consumer market – it may be easier or cheaper for manufacturers to include the same (improved) security measures in all their products, including consumer products.. The development and documenting of minimum security outcomes could also be the first step in developing a trust mark.

3. Industry and policymakers should encourage responsible disclosure of software vulnerabilities in consumer IoT. Policymakers could act to reduce the legal risks faced by security researchers looking to responsibly disclose information on software vulnerabilities they have discovered. Currently such researchers can face legal threats for their actions. Policymakers could create a process for responsible disclosure that reduces the risk that legitimate security researchers will be exposed to legal threats.

4. The industry should develop a trust mark for secure consumer IoT devices. A trust mark will facilitate consumers’ ability to distinguish between devices at point of purchase, and neatly embodies detailed information. It is also a complement to the awareness raising of publicity about cybersecurity issues. It will assist in resolving information asymmetries in the market, incentivise companies to improve security, and establish an industry process to agree security standards. The trust mark might be based on an existing certification scheme or industry initiative. [11]

5. Policymakers should require that consumer IoT devices must comply with a set of security principles. Rather than a rigidly-specified set of prescribed standards, this would involve compliance with various generalised principles – for example, requiring that: – the software/firmware on a device can be updated if necessary; – the device does not ship with easily-guessable default credentials, or credentials that cannot be changed by the user; and – the manufacturer complies with vulnerability disclosure standards. This approach should lead to improved device security while retaining flexibility for the market to innovate and improve on security measures.[12] The principles are more likely to remain future-proof (whereas specific encryption methods may eventually become obsolete) and will also apply to new classes of devices.

6. Policymakers should be more proactive in prosecuting manufacturers or service providers who make misleading claims on security. This measure would provide an incentive to manufacturers to either improve security or provide honest information about the security on their devices. It could also tie into a wider education/publicity campaign. The US has been active in pursuing device manufacturers that mislead consumers about the level of security on their devices.[13][14]

7. If the above actions do not result in material improvements in consumer IoT security, regulators could mandate a minimum set of security requirements for IoT devices. The actions listed above are aimed at improving consumer IoT security without the need for extensive government intervention. However, if industry-led initiatives fail to lead to material improvements in device security, policymakers should be prepared to consider mandating a set of security requirements for consumer IoT, with or without certification.

This represents a logical extension of Action 5. The main distinction is that, under this approach, the security requirements of a product are much more tightly specified at a technical level – for example, specifying a minimum strength of encryption, or certain criteria for the default credentials (e.g. length). This action could be further reinforced by more rigorous testing of products entering the marketplace to ensure compliance.

Minimum security requirements may reduce the risk of a device being compromised, and the resultant costs. However, they may also add substantially to the cost of producing and maintaining devices, which could increase prices and reduce adoption (thus decreasing the benefits of connected device adoption for users and wider society) and/or encourage a “black market” in non-compliant devices.

It is possible that, for some specifications of the minimum security requirement, the costs (in terms of foregone benefits) will outweigh the benefits. It may be difficult to accurately assess these costs and benefits. As a result, it is recommended that this approach is employed only if other measures prove ineffectual.

About this study

This study for the Internet Society assesses the state of security on consumer Internet of Things devices and the economic factors behind the weak security on many devices. It then draws upon these insights to offer policy recommendations for improving device security.

Founded by the early pioneers of the Internet in 1992, the Internet Society is a global cause-driven organisation working for an open, globally-connected, secure, and trustworthy Internet for everyone. With members, chapters and offices around the world, the Internet Society engages in a wide spectrum of Internet issues – including policy, governance, technology and development – to address the challenges facing the Internet today and to shape its tomorrow.

The authors are grateful for the research inputs contributed by the Internet Society, and for its input in reviewing the report.

Notes

[1] https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2017-02-07-gartner-says-8-billion-connected-things-will-be-in-use-in-2017-up-31-percent-from-2016

[2] Ibid.

[3] Hewlett Packard (2015), “Internet of Things Research Study”, http://www8.hp.com/us/en/hp-news/press-release.html?id=1909050 [Hewlett Packard (2015)]

[4] See https://security.radware.com/ddos-threats-attacks/threat-advisories-attack-reports/iot-devices-threat-spreading/

[5] The report’s focus is on consumer IoT security rather than privacy; however, privacy issues may be noted where they also relate to security.

[6] FTC (2015), “Internet of Things – Privacy & Security in a Connected World”, FTC Staff Report, https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-staff-report-november-2013-workshop-entitled-internet-things-privacy/150127iotrpt.pdf [FTC (2015)]

[7] Metropolitan.fi (2016), “DDoS Attack Halts Heating in Finland Amidst Winter”, http://metropolitan.fi/entry/ddos-attack-halts-heating-in-finland-amidst-winter

[8] IBM Security (2016), “The inside story on botnets”, https://www-01.ibm.com/common/ssi/cgi-bin/ssialias?htmlfid=SEL03086USEN

[9] See Section 3 for a detailed discussion of these mechanisms. A subset of mechanisms was selected on the basis that the potential benefits (in terms of improved device security) were likely to outweigh the costs of implementation. From these mechanisms we developed a set of specific, tailored actions for the industry and policymakers to take.

[10] Steve Wood (2017), “The 12 ways that Christmas shoppers can keep children and data safe when buying smart toys and devices”, Access at:

https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/news-and-events/blog-the-12-ways-that-christmas-shoppers-can-keep-children-and-data-safe-when-buying-smart-toys-and-devices/

[11] An example of this is the Internet Society’s Online Trust Alliance (OTA) IoT Trust Framework. https://www.internetsociety.org/iot/trust-framework/

[12] In the UK the Department for Culture, Media and Sports (DCMS) offers “Security by Design” recommendations to industry (see https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/secure-by-design). These formed the basis for an ETSI industry standard (see

https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_ts/103600_103699/103645/01.01.01_60/ts_103645v010101p.pdf).

[13] In 2017 the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) fined Vizio, a smart TV manufacturer, $2.2m after it was found to be monitoring the operation of its

devices without consent https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2017/02/vizio-pay-22-million-ftc-state-new-jersey-settle-charges-it

[14] The FTC also filed a complaint that device manufacturer D-Link left its devices vulnerable to hackers, contrary to claims made by D-Link. Though the

complaint was dismissed by the court, such actions send a signal to manufacturers that there is the potential to be found liable for consumer harm if

they mislead consumers on security, helping to address misaligned incentives in the marketplace. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2017/01/ftc-charges-d-link-put-consumers-privacy-risk-due-inadequate